Whether you’re designing a course or giving learners study advice, don’t let these myths lead you astray.

Many instructors get started in online education because they want to share their expertise with the world. They’re subject matter experts, but they don’t necessarily know a lot about effective teaching methods. And as a result, they’re likely to grab hold of some teaching ideas they’ve heard about but never examined and move forward with them under the misimpression that simply presenting their information is enough to help their learners learn.

Unfortunately, these assumptions are likely to backfire, leading to courses that don’t connect with learners and don’t lead to the outcomes the instructor hoped for. This is bad news to leaners and educators alike.

The problem is that many of these myths seem perfectly acceptable, so we accept them uncritically. I did myself for many of them—until I saw information indicating otherwise. So, in the interest of promoting better learning, let’s review a few of the biggest myths to see if we can eradicate them for good.

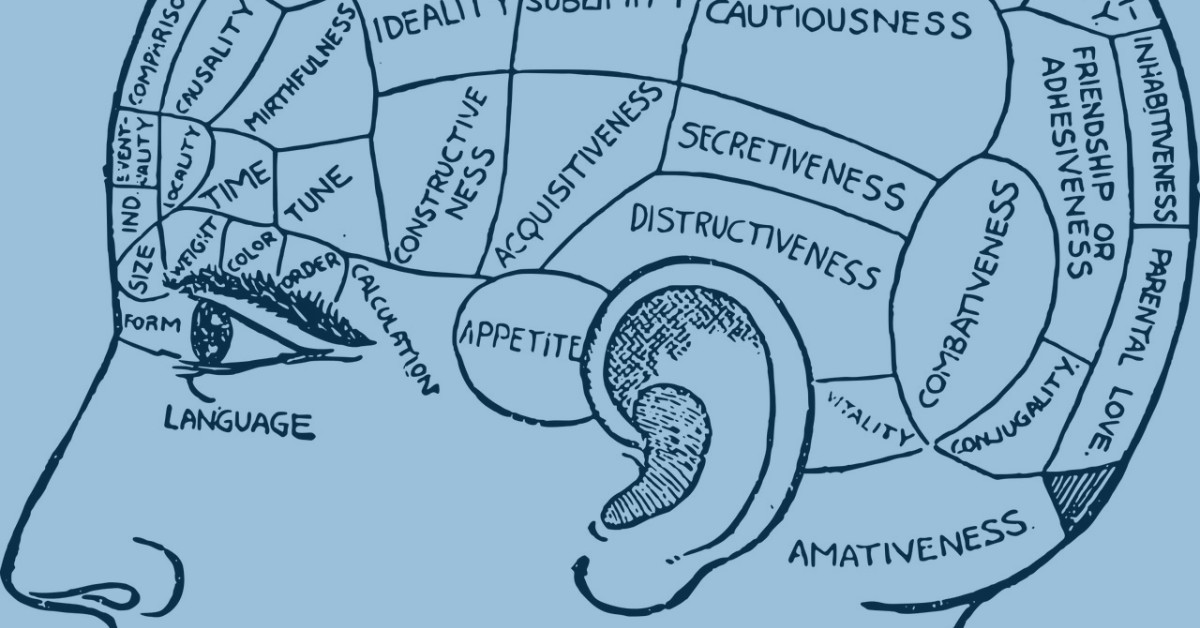

Myth 1: Everyone has a learning “style.”

Let’s start with this one as it is one of the most prevalent learning myths out there. So prevalent, in fact, that most of us accept it as implicitly true without stopping to check if it’s right or wrong.

Unfortunately, there’s no evidence to show that this theory holds any weight. People like to think that they have a special learning style, and some may even have learning preferences, but catering to those preferences does not show any learning benefits. In fact, it may hold learners back if it’s not encouraging them to strengthen other ways they have of absorbing information.

None of which is to say we shouldn’t provide material in a range of styles. The benefit of offering a variety of information types is that it leads to a richer learning experience for everyone.

Myth 2: More studying = better studying.

When learners are struggling with material, they are often told to simply “study harder.” At the risk of sounding trite, the real advice should be “study smarter.”

Simply repeating information over and over does not necessarily help learners understand it. The same thing can be said of cramming before a test: the learner can spend a lot of time memorizing information without being able to reframe it in their own words, or they might cram too much and have most of what they learned to into short-term memory without long-term retention.

Instead, learners should be encouraged to pace their learning, reviewing in short chunks with time in between to help test their recall.

In fact, this is where the design of your course can pay big dividends in learner outcomes. Instead of telling your learners to review the material until they have it memorized, you can deliver short review quizzes at different points in the day that challenge them to recall what they learned earlier. Even better, challenge your learners to paraphrase what they learned at the end of a lesson, to help transition them from passive to active learners.

Myth 3: You’re either “right-brained” or “left-brained.”

Let me just say from experience that this is a very controversial topic for some people. Many of those who have read the descriptions of being right- or left-brained have come to identify with those descriptions strongly. For them, it feels true, therefore it must be true. Telling them that “actually, we all use our whole brains equally” feels like a direct attack on part of their identity.

But, not only is there no scientific basis for the idea that left-brained people are more analytical while right-brained people are more creative, scientists haven’t even been able to find any evidence that people use one side of their brain more than the other at all.

In retrospect, this shouldn’t be surprising. After all, the world is rife with examples of mathematical geniuses who were also highly creative, or artistic geniuses who were highly methodical. And while certain people might be more or less creative or methodical, we shouldn’t pigeonhole them by designing our courses to play to unfounded learning biases.

Myth 4: Learning gets harder as you grow older.

It’s time to retire the phrase “you can’t teach an old dog new tricks.” As it turns out, there’s plenty of evidence to show that we retain brain plasticity as we age, meaning your older audiences are just as capable of learning as your younger once.

More importantly, these audiences want to learn, and feel frustrated when they are boxed out of the educational market simply because that market assumes they won’t use technology. They can, and they will—so long as you let them.

Myth 5: People remember 10% of what they read, etc.

Edgar Dale’s Cone of Experience is often referenced as shorthand for the value of certain types of learning materials. The idea is that people only remember about 10% of what they hear, but 20% of what they hear, and 30% of what they see—so on and so forth.

This neatly ties in with the “learning styles” myth, but with an added dose of prescriptivism. Not only are learning styles a thing in this model, but some are even better than others!

The problem is that the original model was never meant to express this. Learning simply doesn’t break down into neat numbers, and the experiences of individuals are much more complex than can be summed up in a pyramid graph, as visually appealing as it may seem.

What does seem credible is that learners remember information the more they are able to move it from passive to active memory. Reading a book, watching a video, or listening to a lecture are all passive activities. But taking a quiz, writing an essay, or delivering a presentation are active.

Obviously, a learner can’t jump straight into delivering a speech until they’ve learned the subject matter. You can’t tell me what a book is about until you’ve read it. But the process of turning a passive experience into an active one is powerful, so the more you, the instructor, are able to engage that part of the learner’s brain, the more it is that that knowledge will stick.

The way you structure your course matters.

We’ve covered a lot of myths, but if there’s one thing we should take away from this, it’s that the way you teach matters. You can improve learner outcomes by designing a better course, and a lot of the principles can be applied using the tools available to you in our LMS.

Want to encourage learners to review content in small bites throughout the day? Send them some dripfeed quiz content. Want them to use active learning instead of passive learning? Write quiz questions that require more critical thinking. And above all, don’t put learners at a disadvantage by playing in to generational stereotypes.

And last of all, have fun designing your course! The more you learn about learning, the more exciting teaching becomes.

LearnDash Collaborator

@LearnDashLMS