Learning Game Design Series, Part 8: Dump ADDIE; Iterate Instead

Learning game design is a VERY iterative process. It’s not an approved design document, two drafts plus final—or design, alpha, beta, and gold master.

This post describes (and shows) the iterative design process required to create an effective learning game. I define “effective” as a game that 1) achieves the learning goal set for the game and 2) players describe as engaging or fun to play.

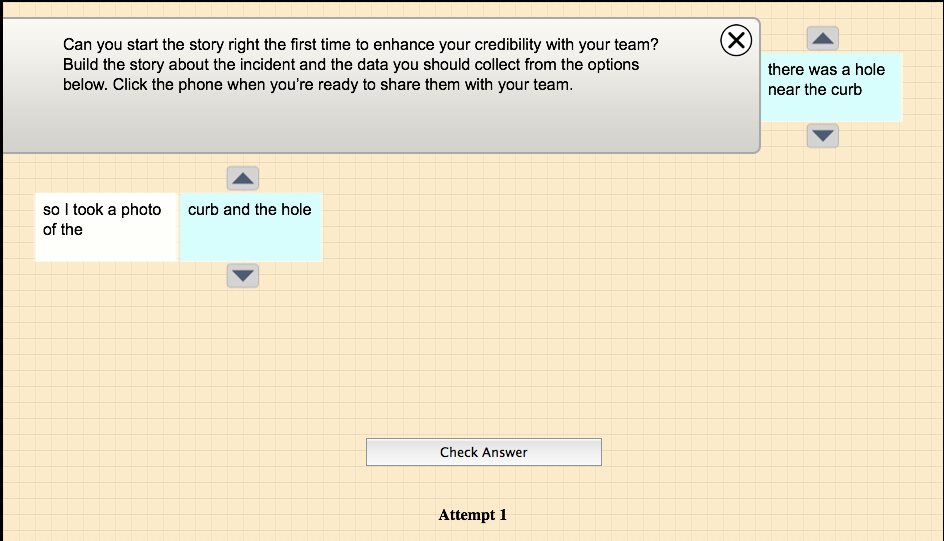

Version 1

We have a project going on right now that includes several different “mini-games.” Below is an early prototype for one of them. (It’s the first version beyond the initial paper prototype.) In its first programmed version, it was called “Story Shuffle.” The learning goal was to be able to identify the data you need to collect as part of an incident investigation.

Note that even this early version includes content. Unlike other kinds of learning designs, a game has to include content from the beginning. When we “played” this initial programmed version (v1) we quickly decided it wasn’t fun – and wasn’t “game-y” enough to suit us.

Version 1.1

We brainstormed—and came up with a new way to approach the game—but we thought we could streamline our process by NOT putting in the content. Instead, we thought we’d do the Michael Allen SAM approach and just build the interaction out so we could see if we liked it. Here’s our V1.1.

We had five people play test it, and all of them concluded: “We can’t tell whether it will be fun or not because there is no content.” We also have no idea what it will look like aesthetically. If you remember from my game elements post, the aesthetics are part of the fun factor. We need something to show us what this game will “feel like.” Our lesson learned. With learning games, real (or at least realistic) content has to be part of every iteration because you can’t assess the game without it. We also agreed that, for us, art assets need to be included relatively early so playtesters get a sense of the look/feel of the game. Aesthetics are too important of a game element to not start fleshing out early.

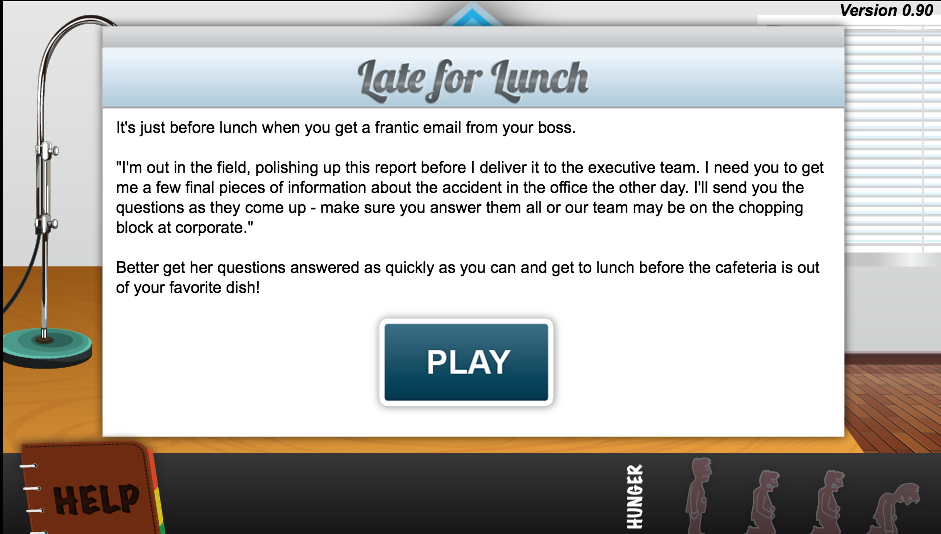

Version 1.2

Here’s V1.2 of the game, now renamed “Late for Lunch.” The game goal is to get to lunch before you pass out from hunger. The learning goal is the same: to be able to identify the appropriate data to gather for an incident investigation.

In this version—which is still not done—we included aesthetics. Our testers concluded this version is pretty good, though we still have more revisions to make. In contrast to the previous version, we now have CONTENT, which lets us evaluate the playability of the game. Never again will we try to shortcut and omit content from an iteration of a game.

As you iterate in learning game design, consider this as a possible sequence for a digital game. If it’s not a digital game, then you obviously won’t create digital outputs. You’ll simply keep refining the components of the table-top game:

- Conduct Game Design brainstorming meeting. Define your instructional goal and objectives, your audience characteristics, select a theme, a game goal, and a core dynamic. Identify possible content you can include. Build a paper prototype, including some content that would actually appear in the game.

- Play test this paper prototype in the game design meeting. Document player reactions; identify the first list of revisions.

- If revisions are extensive, build a second paper prototype. Playtest again. Identify revisions.

- Build initial digital version of game, perhaps in PowerPoint. Create enough art assets to give testers a sense of the game’s theme and look/feel. Include enough content that playtesters can evaluate the game for its fun factor and its learning value.

- Play test this digital version with 3-4 play testers. Document feedback. Determine next steps. If needed, revise this digital version again. Play test again.

- Build initial programmed version (V1) of game with enough game levels or game loops within it for players to fully experience the game mechanics and assess the core dynamic. Include sufficient content to support the levels or loops you create. (If your game is going to have multiple rounds or levels of play, this means you don’t develop ALL of them – you develop enough to let players assess the playability and learning efficacy.)

- Play test. Document feedback. Determine next steps.

- Revise to V1.1. Play test again.

- Etc. When we go “live,” we are at V2.

How far do you iterate?

How far do you go with the iterations? You iterate until you get satisfactory answers to these questions from players who truly represent your target audience:

- What did you learn? (Responses should mirror what you wanted them to learn.)

- Did you remain engaged in the game throughout play? (You want a “yes,” here.)

- Did anything confuse you about game play? If so, what was it? (You want to unearth any major confusion. You may not act on everything someone finds confusing. It depends on how many people cite it as a problem, and if the confusion hinders learning or engagement.)