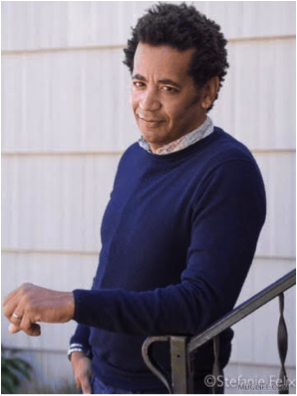

Photo courtesy of Arts Corps

Teaching is like dancing. Sometimes your step on someone’s feet, misread cues, or land flat on your ass. Whatever the case, teaching is both exhilarating and frightening. Even on the best of days, there’s always one thing that tickles your brain because you know you could have done something better. Now that many of us are teaching and parenting and stuck in close quarters 24/7, teaching has become more multilayered, and sometimes even more frightening. I have two 10 year olds that, though twins, are more different than they are alike. They have different interests, skills, and temperaments. One likes to act, one likes to dance. One is a great storyteller, and one is amazing at math. They have/had different teachers in 5th grade and they both have weekly hour-long Microsoft Teams video chats with their teachers at different times and different days. The teachers are trying their hardest to reach all of their students, but we all know that is sisyphean in their efforts. At no fault of their own, we, parents, have to take up the mantle of teaching during these days of quarantine. Though my background as an educator serves me well as the Executive Director of the education organization, Arts Corps, that doesn’t translate when teaching my own children. Luckily, my wife is an amazing partner in this dance of teaching, and I am following her lead.

But for the first couple of weeks of quarantine we were doing completely different dances. While she was doing the Tango, I was doing the Lindy Hop. We were balancing 6-7 hours of teaching, 16 hours of working, and 24 hours of parenting. We were not sleeping and stressed out to the nth degree. Arguments, questioning, quitting, starting again, and giving up again. Over and over again. After some recalibration, we decided what our children needed to succeed, and what we needed to maintain a sense of normalcy, was to slow down the tempo of our dance. We carved out time to work on physical workbooks, Barbies, online games, Lego, laying on the couch, puzzles, and lots and lots of art making. We hadn’t found the perfect rhythm, but we were making strides towards better choreography.

Then, only two weeks ago in early April, 80s hip hop star D-Nice, started to deejay on Instagram Live and we were drawn to listen and watch. Other deejays followed like Questlove of The Roots and the Tonight Show fame, Lord Finesse, 9th Wonder, DJ Premier, Oshun, and The RZA to name a few. They all started saying the same thing: “It’s a vibe.” To translate from the vernacular, “a vibe” meant we were on the same energy to coexist easily. The musical energy coming out of our speakers helped us find our vibe. It helped us acknowledge the good parts of the day. It helped provide some perspective on the days that seem to endlessly repeat. These deejay sessions further illuminated why the arts are essential to our personal and educative lives.

I realized the arts have always been essential throughout our history. During the Great Depression of the late 1920s and 1930s, 25% of the US was unemployed – about 13 million people. The state of Georgia laid off almost all of their teachers. Twenty percent of NYC students suffered from malnutrition. The stock market lost 90% of its value and hope was generally lost. Not long after Roosevelt took office in 1933, he established the Works Progress Administration (WPA) to support those unemployed. Out of the WPA came many federally funded arts projects meant to benefit our society. Roosevelt’s reasoning was that just like construction workers and farmers, artists also needed to eat. This funding not only led to still famous murals in federal buildings in big cities, it also brought theatre, music, and visual arts to rural and other marginalized communities. Traditional Native, African-American, and Quaker dances and music was able to be documented for future generations to enjoy. The New Deal brought us artists such as Richard Wright, Georgia O’Keeffe, Diego Rivera, Orson Welles, and more. As Roosevelt, the author of the New Deal, said: “Art is not a treasure in the past or an importation from another land, but part of the present life of all living and creating peoples.”

While the New Deal was able to support the art of the time to reflect on our past and present, it helped shine a light on the inequities in the USA. In 1933, many US residents were illiterate and did not possess basic job skills. Hence, remedial classes were offered to individuals to help the unemployed get the technical vocational jobs available. The National Youth Administration program was established to keep young people in school by providing them with part time work as janitors, librarians, clerks, and working on construction sites. What was most amazing to me is that this extended to Black people and other people of color who were provided with jobs and training, and paid black students the same as white students. This was during a time of Jim Crow laws, before integration (1954) and before we had the right to vote (1965).

Historian Paula S. Fass noted that though much of what the WPA enacted was temporary: they “demonstrated that the federal government could do what established agencies had failed to do,” and that the New Deal “changed the meaning and nature of all future discussions about the federal government and education.” The New Deal was creating the ‘vibe’ for how the USA would exist then and how it would be perceived today. To have a ‘vibe’ you need to have a reference point, something to which everyone is able to relate. Job training, education, the arts, and more equitable tax structures helped establish that ‘vibe’.

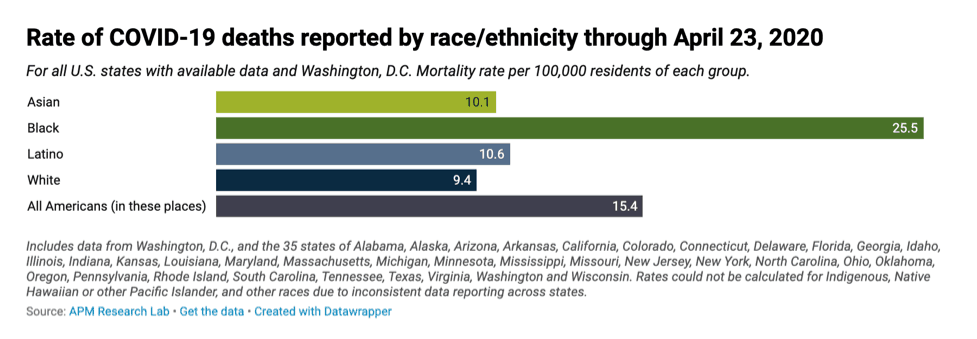

In the 1930s, contrary to what is happening now almost 100 years later, relief went to people rather than organizations because leadership then understood that humans, and not businesses, make up the infrastructure that runs our economy. Today big businesses, as they were in 2008, are provided with more relief than the individual. The current aim seems to prefer increasing stock buybacks and bonuses to executive salaries, rather than increasing access to housing, health care, and food. Those on the “margins” like people of color, immigrants, queer and trans, rural and low income communities are suffering more. Undocumented immigrants aren’t able to receive aid or relief from the federal government, and still have to fear detention and deportation based solely on their status. Regulations set up to protect LGBTQ discrimination in healthcare will probably be eliminated, allowing for hospitals to deny health care because of a patient’s identity. Celebrities and politicians are able to be tested, yet the average citizen has to wait to be tested, or aren’t even able to be tested. Black and Latinx people are dying from COVID-related illnesses at a much higher rate than their white counterparts. In Chicago, Illinois, for example, Black people make up 72% of COVID-19 related deaths, though they make up less than 33% of the population.

Two thirds of artists are unemployed and that will probably increase as the weeks progress. According to the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), “the arts contribute more than $760 billion annually to the US economy, which is more than sectors such as agriculture or transportation. Yet, only $250 million was allocated to support the arts in the emergency aid bill passed in March.”

That’s not a vibe.

Since the dawn of time, the arts have been integral in human existence. Beginning as a way to communicate and pass down stories through generations, the arts have been able to capture the zeitgeist of the times, as a way to creatively tell our collective history. During the Dark Ages of Europe, the “rebirth” that the Renaissance represented was based in the expression of its artists. In the way da Vinci was able to reflect the humanistic ideals of Europe at the time, we have today’s artists. Like those mentioned above and others, they are able to synthesize our world through creativity and shape our lives moving forward. Writer and illustrator Mo Willems has a lunch time doodle club, where young people and adults are invited to virtually draw alongside him. A group of regional theatres across the country started playathome.org where they commission new and upcoming playwrights to write plays to be performed in their homes. The TV show, Saturday Night Live, is broadcasting their zany brand of humor to audiences from the individual homes of the writers and performers. Theatres around the globe are streaming plays for audiences to watch from the comfort of their own homes. Dancers, musicians, visual artists, comedians and yogis are all teaching their art forms on social media.

Image courtesy of Arts Corps.

At Arts Corps, we have pivoted our programming to teach arts enrichment and arts integration classes to youth aged 5-18 years completely online. We are making video lessons for families to engage with at their leisure. We have created online booklets of arts activities for families to use, as well as coloring books that help reflect on our everyday. More than half of US students aren’t participating in online classes, and like all over the US, many of the families we serve don’t even have reliable access to the internet. So, we have created arts kits that we are able to drop off in coordination with local school districts, at the sites where free lunches are dropped off. Many arts organizations across the USA are doing something similar, and all of us are doing our best. Yet, we should not have to do the work that our federal government refuses to do. Like teaching, leadership is also a dance and the federal government is not being a good partner. This is not a political statement, pitting one party against the other. It’s a human rights statement. We deserve basic human rights like housing, food, education, and the arts. I know that it wasn’t rosy back in the 1930s, but at least there was an effort on the part of the USA to take care of its people. Can the same be said for 2020? What will people in 2120 say and think about how we treated each other during this pandemic? Right now, I’m afraid that it wouldn’t be positive. We have a chance to turn it around to actually invest in people, invest in the arts, and invest in the future. When government policy invests to create the energy to coexist easily, then it will truly be “a vibe.”

About the Author:

James Miles worked as an educator in the New York City public schools for 20 years before joining the Seattle-based Arts Corps as Executive Director. Originally from Chicago, Miles has worked internationally as an artist and educator, and his work has been featured through Complex magazine, National Guild, The Seattle Times, KOMO, NPR, CBS, NBC, the U.S. Department of Education and ASCD. Miles is a Mayoral Appointee to the Seattle Arts Commission, and on the advisory board of SXSW EDU. His acclaimed TedXTalk focuses on his mission to narrow achievement gaps using the “arts as a tool to navigate the systems of educational inequity”.

In this post, James Miles reminds us that in an earlier age it was Richard Wright, Georgia O’Keeffe, Diego Rivera and Orson Welles who transformed the ways we understand and act in the world. Work of such insight is never lazily acquired; it flows from methodical study and reflection. Join the thousands of learners engaged in such deep learning by taking our popular courses in Cinematic Storytelling, Introduction to Graphic Illustration, Generative Art and Computational Creativity and Comics: Art in Relationship. You may even want to begin Charting the Avant Garde: From Romanticism to Utopic Abstraction amid the reality of COVID-19. Join for free or become a Premium Member to unlock exclusive lessons and learn without limits!