Lecturer and researcher Adam Ritchie spent his high school years in detention with school report cards describing him as smart but unfocused, playing in class and causing trouble.

Years later, he is an accomplished academic at the University of Oxford who played a major role in the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine distribution, saving millions of lives.

In high school, Ritchie didn’t always get along with others, getting into the habit of fighting with the boys, which got him a few suspensions and hours of detention.

“People would say I was a bit of a class clown or maybe an attention seeker who got in a little bit of trouble,” Ritchie told Education Review.

In addition, school bore him, and he found himself often distracted and unfocused on the lessons, hiding at the back of the classroom to read a novel.

Yet, in Year 10, things turned around for the future academic: his science teacher, Julie Carrington had the class take on the International Competitions and Assessments for Schools (ICAS), an online international competition for high achieving students.

The teacher had always loved these kinds of tests which evaluate students on their ability to apply classroom learning in real-world scenarios using problem-solving skills.

Ritchie said she and the school believed these tests helped uncover potential and untapped talent within the classroom.

The future academic remembers thriving during the ICAS assessment as he found them more stimulating than the ordinary classroom test and ended up achieving a perfect score that year.

For the school, Ritchie’s ICAS results highlighted that he wasn’t ‘just’ a tedious teenager, he had potential.

“After the school got the test results, someone came into my classroom and there was a note that I had to go and see the deputy principal and I remember thinking 'Oh, God, what have I done?'

“I really just remember the principal telling me 'Adam, what are we supposed to do with you?'" he said.

The principal went on to tell Ritchie about his perfect score in the science exam, congratulating him at the same time as being frustrated by the young man.

Later that same day, the principal saw Ritchie in detention once again, as he was picking up rubbish in the garden, he recalls the educator calling his name, looking at him, shaking his head and walking off.

“I remember a strong sense of maybe I should be doing a little bit more,” he said.

If Ritchie’s educators were somewhat exasperated with his behaviour they believed in the young man's potential.

The team decided to enrol him in an academic program with the University of New South Wales where he was paired up with a palaeontologist.

The program gave him the opportunity to spend some time on excavation sites where the researchers were looking at the association of megafauna with early First Nations people from Australia.

Ritchie believes that his teachers knew at the time the experience might be interesting and eye opening for him, as he immediately started paying more attention in class and became a better student.

According to the researcher the interest that Carrington and other teachers gave him helped shape his future career.

“I think that interest from Julie scaffolded for me, she taught me how to become a creative learner and thinker.”

“I actually started linking science, and thinking about what the future may look like, and maybe I’d be able to do something in the field that will have a little bit of an impact in the world.”

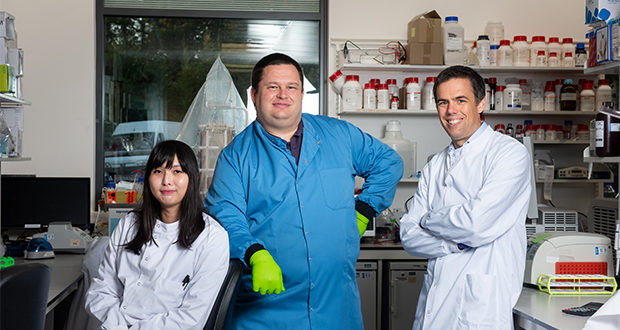

Following his first experience in academia, Ritchie went on to study microbiology and immunology at UNSW and graduated with a PhD in immunology.

He then moved to Europe in order to follow his passion for football while becoming a lecturer at the prestigious Oxford University, where he has spent the last 17 years.

It was in 2020 when Covid-19 hit the world by surprise that Ritchie’s career would take a turn.

He had long been convinced that his students would be successful academically, not himself.

“I think Julie rubbed off on me, I am always looking for untapped potential in my classes.”

At the time when the first cases arose, Ritchie was part of Oxford's medicine department as a rabies vaccine project manager in charge of developing the manufacturing process.

While the pandemic quickly spread, Ritchie was tasked to manage a new program to ensure the development and delivery of the manufacturing process for the Covid-19 vaccine in development.

“It accelerated so fast that a few weeks later there were about 400 of us involved,” he said.

A couple of months after starting their work, AstraZeneca joined the team and took the vaccine process to the next level.

With the help of AstraZeneca, the researchers scaled the vaccine up and transferred the knowledge to manufacturers worldwide, including Australia.

According to Ritchie, a lot of the lives saved by the vaccine are due to the manufacturing process, which was an important element of the AZ vaccine and allowed it to be rolled out in many countries in a relatively short period of time.

As of today, the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine has been used in 185 countries, and more than 2 billion doses were distributed less than a year after its approval.

In Australia 12.6 million of AZ doses had been received by October 2021.

“To think that we saved millions of lives just in the first year, some people are walking around and wouldn't be here [without the vaccine], that's pretty humbling at the same time as being a very pleasant sort of thing.

“It is that which I fully expect to be the most important thing that I'll ever do in my career,” he said.

While Ritchie aims to continue his academic career, he believes the ICAS test and Carrington’s attention played a major role on what his life looks like today.

“I'm sure I'm not special," he said.

"I think teachers like Julie and others care a lot, they are trying to invest and show an interest in lots of their students while it is a difficult job at times for limited financial rewards.

“I know the particular interest that was shown in me has helped me do what I do today.”

Do you have an idea for a story?Email [email protected]

Education Review The latest in education news

Education Review The latest in education news

It was such a privilege to be able to have Adam in my class.