Instructivism is dead. Gone are the days of an authoritarian teacher transmitting pre-defined information to passive students.

In the 1990s, constructivism heralded a new dawn in instructional design, turbo-charged by the rise of Web 2.0. Students morphed into participants, empowered to seek new knowledge and understanding for themselves, in the context of their own unique, individual experiences.

In turn, teachers enthusiastically transformed themselves into facilitators, guiding and coaching the participants to inquire, explore, discover and even generate new learnings.

Fast forward to today and connectivism is all the rage. In this digital era, we recognise that there’s simply too much knowledge to take in – and it changes too quickly anyway. So forget about trying to “know” everything; instead, build your network of knowledge sources, and access them whenever you need them.

Slippery slope

The popular sequence of events that I have recounted is often represented pictorially as a gradient, accompanied by that ubiquitous table comparing various aspects of the three pedagogies.

![]()

But is this gradient a fair representation?

Certainly it’s accurate in terms of chronology: the concept of constructivism was conceived after instructivism, and connectivism was conceived after that.

However, I think the diagram misleadingly suggests an evolution of instructional design. In other words, constructivism was so intellectually and pedagogically superior to instructivism that it replaced it, and connectivism is so intellectually and pedagogically superior to constructivism that it, it turn, has replaced that.

Sure, the gradient reflects a wonderful growth of ideas, but I think it’s a trap to conclude that the latter pedagogies supersede the former.

The real world

My view is informed by observation.

Yes, workplace learning has thankfully become more constructivist and even connectivist over time, but we all know that instructivism is still alive and well.

For example, face-to-face classes with monologous trainers and one-to-one coaching sessions remain popular modes of delivery. Even in the e‑learning space, online courses are typically linear, virtual classes frequently replicate their bricks-and-mortar antecedents, while podcasts, of course, are quintessentially instructivist.

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

Why is this so? Why, in the midst of ever-advancing learning theory and progressive instructional design, does such rampant instructivism persist? Why haven’t constructivism and connectivism blown it out of the water?

The answer, I believe, is because instructivism remains relevant.

The three amigos

Allow me to elaborate my argument in the context of the financial services industry.

When a new employee is recruited into the organisation, there are certain things they just need to know. For example, it might be imperative for the employee to understand how the superannuation system works, or a particular taxation regime, or the regulations that govern a particular investment option.

Not only does a sound understanding of the fundamental concepts have an obvious bearing on the employee’s ability to do their job properly, but leaving such learning to chance could have serious risk management and compliance ramifications.

This is where an instructivist approach proves useful. Whether in a classroom setting, via an online course or otherwise, the resident subject matter expert (SME) within the organisation typically provides the learner with a programmed sequence of knowledge, carefully scaffolding their learning and – to adopt a cognitivist view – construct a basic framework of knowledge in the learner’s mind.

As a novice in the domain, the learner is unlikely to know what it is they need to know. The SME transmits this necessary information quickly and efficiently.

Next, a constructivist approach empowers the learner to expand and deepen their knowledge at their discretion. For example:

- Discussion forums (synchronous or asynchronous) allow the learner to ask questions, clarify concepts and share experiences.

- Wikis act as non-linear knowledge banks to be mined as necessary.

- Search engines allow the learner to follow their own trails of inquiry.

No longer a novice, the learner has the tools to drive further learning in the context of their existing knowledge.

As the learner acquires expertise, we must recognise that in this digital age, no one person can ever be expected to know it all. At this point, a connectivist approach empowers the learner to extend their knowledge by proxy.

In a previous article, I provided the following examples of potential information sources that the learner could incorporate into their personal learning network:

- Social bookmarks

- News feeds, podcasts, blogs, wikis and discussion forums

- Social and professional networks such as Facebook and Twitter

- Industry conferences and other external events

In today’s environment, I see an expert as one who couples a rich foundation of knowledge with the capability to connect to new knowledge at a moment’s notice.

A new representation

In the workplace, it’s clear that instructivism, constructivism and connectivism are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

The astute e-learning practitioner will apply principles of all three, as circumstances change and their respective relevancies rise and fall. As I have suggested, this may align to the learner’s transition from novice to expert in a particular domain.

From a practical perspective then, is the popular “evolution” of instructional design from instructivism through constructivism to connectivism a furphy? All three pedagogies build on one another to provide a rounded theoretical toolset for the modern professional to exploit.

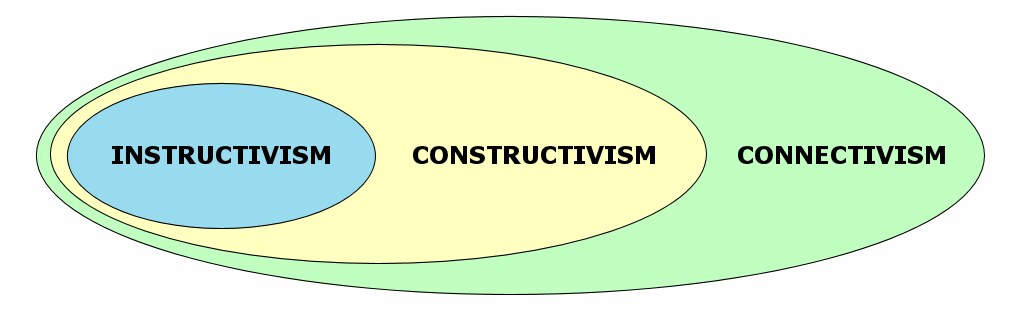

Therefore, I propose to replace the traditional left-to-right gradient with a new representation:

This diagram acknowledges the chronology of instructional design theory, with the earliest pedagogy occupying the centre circle, and the later pedagogies occupying the outer rings. Yet it does not suggest that one pedagogy supersedes the other; instead, they complement one another.

Balancing act

It’s important to point out that in any organisation, different employees will be at different stages of learning across multiple domains. The instructional designer will need to balance all three pedagogical approaches to support everyone.

For example, while an online course may be purposefully instructivist to support novice learners, it’s important that a learner-centered approach be adopted to serve others who may also use the course (or parts thereof).

Conclusion

In short, if someone asks me “Instructivism, constructivism or connectivism?”, I say “All three, where relevant”.

“The answer, I believe, is because instructivism remains relevant.” Yes, yes, yes. Thank you Ryan.

Great post. I really appreciate the intersect between all three elements. The idea that information is changing so fast is apparent in my work as well. How do we prepare learners when the content changes faster than the update can be pushed to the LMS? Prepare the learner for the unexpected… more of a toolbox to use when they need it.

Thanks again.

Excellent post and very relevant. My observations also validate that one approach does not replace the other and that the three approaches represent an evolution of learning that can almost happen in a simultaneous space. So in other words, instructivsm, constructivsm, and connectivism are more likely to explain the evolution of the person than the evolution of instructional design.

Connie Malamed

theelearningcoach.com

hear hear re: instructivism. its a relevant part of the learner’s journey.

your post reminded me of Gilly Salmon’s e-Moderating model. Instructivism is relevant in certain contexts, and sometimes as a way of moving learners toward more self-directed activities, and eventually toward connectivism and the type of knowledge that creates.

I think an understanding of the relationships you’ve highlighted is required at the learner and at the trainer level as it can be a really scary transition for both.

Nice post BTW

Here’s a link to Gilly Salmon’s model if you’re interested http://www.atimod.com/e-moderating/5stage.shtml

Ryan, why have you left out sociocultural learning? Especially for the workplace, the concepts of situated learning and communities of practice are essential.

In this concept, information, facts etc in the form of presentations, readings etc are important, but they are made relevant as the novice learns to integrate this into their own knowledge base as they work with more competent people such as their superiors at work.

This is because, as some propose, learning is mediated and needs other more expert people to help us internalise knowlege and make it real, usable and relevant.

I think western thought is so individualistic that they have not ever really grasped the siginficance of the more social concepts of learning theories but these are really needed for workplace learning. However, they help provide a good foundation for connectivism.

Have a look at some work by John Seely-Brown, eg Situation Cognition, and a later one called Minds on Fire

woops- situated cognition i mean

Good question! I suppose I was focusing on overarching pedagogical philosophies rather than specific learning theories or metaphors. I am indeed a supporter of the principles of situated learning and CoPs, and I agree with your view that they are highly relevant to the workplace setting. An important aspect to consider is how any one particular community operates: do the experts tell the novices the way it is (instructivist), are the novices allowed to freely ask questions, challenge ideas etc (constructivist), or does it operate somewhere in between? Andrea, I’d love your feedback on my latest article, Taxonomy of Learning Theories, in which I mention Situated Learning Theory: http://is.gd/6e6RX

Hi Ryan,

Sorry for slow reply, I lost the link.

Your Taxonomy looks great and easy to understand, nice to see people looking at theory, not just technology.

However, I (& I am prob in the minority!) would put socioculturalism- if it is a word beside constructivism, or put the two of them under a main category of active learning, which i think was developed through the work of Anglestrom. Both constructivism & sociocultural(ism, theories) say that learning is an active process, both say the social bit is important. However they differ in that, at its heart, constructivism proposes that learning is ‘individually’ constructed, that knowledge is an internal thing. Sociocultural theories (vygotsky) say it is impossible to learn without the social environment (so v. is not a constructivist)so it is a community thing, tho the individual is still impt.

Out of this work, other theories were developed such as cognitive apprenticeship, COP, situated cognition, authentic learning etc. And I think this is much more aligned to connectivism- like the preceeding concept. How this fits together, I am not sure, but as for practice- it means that we need to provide lots of learning in a social environment, and provide the kind of scaffolding and expert support learners need to take them to the next level.

I certainly don’t disagree with you, Andrea. You make an excellent point about constructivism proposing that learning is individually constructed, that knowledge is an internal thing. It links to cognitivism in that way, exemplified by the schema-based work of Piaget.

I suppose I’m a cognitivist at heart, placing the socio-cultural stuff under the constructivist umbrella, effectively subsetting the environmental dimensions under the overarching brain-based pedagogical philosophy.

It just goes to show how significant perspective is in all this. Taxonomies, philosophies and of course theories are all human concepts, and everyone has their own POV dependant on their needs, goals and contexts.

There’s hundreds of ways to slice and dice the domain, and they aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive. Perhaps you might consider drafting your own taxonomy of learning theories, emphasising the sociocultural aspect? If you do, please let me know!

While all the three elements are very relevant and compliment each other, there is another component, the instinctive learning, that is not fully understood yet. How a three year old, for instance, picks up complicated language skills with a very limited exposure to it is a case in point of how instinctive learning happens.

Narayanan

Hi Ryan,

Great post, enjoyed it. Wrote this a while ago now, which very much chimes in with they way you were thiking about this issue. i attempted to bring the socio-cultural learning theories into my model of understanding.

http://learnadoodledastic.blogspot.com/2006/11/externalize-externalize.html.

To note. i do believe the externalisation of knowledge is a difference in determining whether connectivism is a new learning theory. I am also coming around to thinking that we can and do learn internally through a mental process of connecting. Still lots to consider!

Thanks Steve.

I really enjoyed reading your article too, and I think the mental map you added is particularly useful.

Whether connectivism should be labelled a learning “theory” or not, I don’t know. However one thing is clear: the socio-cultural aspect of learning is growing in importance in terms of making sense of the modern-day avalanche of information.

I don’t think the connectivist philosophy is mutaully exclusive with the cognitivist or constructivist philosophy of internalising knowledge. I feel that talking to peers, reading blog posts, listening to podcasts, participating in forums etc are all part of defining and re-defining meaning (which is internalised as knowledge).

The externalisation of knowledge is a must given that there is so much of it. The trick (I think) is not trying to “know” all that, but rather know *where* it is so you can get it when you need it.

I’ve enjoyed reading your article and I myself started some reflection upon the issue to be talking about it with the school coordinators I work with.

Thanks

Marcia

Thanks Marcia, glad to hear it.

Reblogged this on Profesora Anaylen López.

Hi Ryan, great post! I find your argument relevant for pedagogy but I’m uncomfortable with the contrasting of learning theories or saying that each is ‘complimentary’ because they are, as theories, each mutually exclusive. I know I’m probably in danger of preaching to the converted here, but these are cognitive theories explaining how people learn, they will learn regardless of how we teach and they won’t always learn what we intend, so, as theories they attempt to explain the cognitive process of learning and not necessarily the process of teaching or the designing of learning environments. “Instructivist” teaching could and work if, say, constructivism as a theory was ‘true’ because whilst the student might attend an “instructivist” class they may still build their knowledge themselves whilst away from class or whilst speaking to their peers in their CoP. I think it’s erroneous for teachers to ‘recreate themselves’ as you say to fit a cognitive theory because it is attempting to explain how a person learns, not necessarily how to teach or design for learning. I think it might be better to contrast teaching styles or approaches without using theory as a descriptor because theory informs our design but does not define it and so I’m not sure if its helpful to try to reconcile contradictory theories.

Thanks for your comment, Paul. Stephen Downes mentioned something similar on his OLDaily recently: http://www.downes.ca/archive/14/03_21_news_OLDaily.htm

Indeed, I’ve made a point of referring to instructivism, constructivism and connectivism as “pedagogies” rather than as “theories”, as I think the latter can be problematic. For example, as you are no doubt aware, the question of whether or not connectivism is a theory has been somewhat controversial – eg: http://www.scribd.com/doc/88324962/Connectivism-a-New-Learning-Theory

If we call these concepts theories for the sake of convenience, I don’t necessarily agree that they are mutually exclusive. Stephen states “According to instructivism, knowledge can be transmitted. According to constructivism, knowledge is created via internal representations.” This begs the question, why can’t knowledge be transmitted and converted into internal representations?

Consider a Java programmer who has several years’ experience in her domain. On the basis of her prior knowledge, she posts a question to an online forum which reflects a specific personal learning need. Many would say this is an instance of constructivism. If someone answers her question, to me that is a transmission of knowledge. The same may be said if she searched for a relevant clip on YouTube and watched an expert explain it.

The fact that she knows those sources exists (connectivism) does not preclude the transmission of the knowledge and her subsequent assimilation of it into her existing cognitive framework.

Yet even in writing this, I can’t help but dislike referring to these concepts as theories. I prefer to think of them as lenses through which we view the same thing – ie learning. To extend the analogy, if we all wear different coloured glasses, we’re looking at the same world around us. My pair of glasses doesn’t disprove your pair of glasses; we simply see the same thing differently, or perhaps we are looking at different parts.

I agree with your view that instructivism, constructivism and connectivism attempt to explain the process of learning and not necessarily the process of teaching or the designing of learning environments. However, I suggest that if you have insight into the former, then that is wonderful intelligence to inform the latter.

May I emphasise that I have the utmost respect for Stephen, and also for yourself for taking the time to comment on my blog and voice your own point of view. Of course, our views don’t always need to align, and in fact it’s when they don’t that we continue the discourse and evolve one another’s thinking. So cheers!

Thanks for your reply Ryan, its been some months since I wrote my comment and I somehow missed your response until now! Your definition of transmission is unusual, since you give an example of a post on a site like stackoverflow.com as ‘transmission’. This certainly is transmission in the sense that a message has been sent from one IP address to another but it misses the human element of interpretation.

Regardless of whether this is instructivist ‘theory’ or ‘pedagogy’, the usual meaning of transmission in learning is in the cognitive sense, that is, that a perfect representation of a schema or construct is ‘transmitted’ into the brain of the learner. A forum response is read by the learner so there is room for error in interpretation, as there is in the wording of the post by the author. Nothing can guarantee that what is ‘transmitted’ is actually what ends up in the brain of the learner because of the amount of ‘noise’ in the transmission and additional information, gleaned from previous experience, added in interpretation. This is why so often learners misunderstand even though they may have had something explained many times and I think this is the crux of what constructivism (and I think connectivism) tries to address.

In time, as a learner becomes more acquainted with a community of practice I think this ‘noise’ lessens but interpretation is always there and misinterpretation is still a possibility. This is why I don’t buy into instructivism myself. I develop instructional materials that will be used and interpreted and discussed by the learner, but I would not expect the contents to be ‘transmitted’ into their brain, all I can do is explicate the material and give as many examples as possible to allow them to develop an accurate interpretation that will work for them.

I don’t know Stephen Downes personally (although I do read his OLDaily) and his perspective in the link you provided did sound similar. I agree with your theory as ‘lense’ analogy and I don’t think this is about ‘proving’ or ‘disproving’, I just think we need to have a consistent terminology in terms of the semantics we use in regard to learning and knowledge. Oh and sorry for the very late reply!

No need to apologise, Paul, and thanks again for another thoughtful comment.

I agree with most of what you have stated, but I am stuck on your explanation of transmission. In my stackoverflow example, I did indeed mean in the cognitive sense, not electronic. Having said that, I didn’t have in mind the perfect replication of the schema into the learner’s brain. Implicitly I acknowledged that the learner would naturally interpret the transmission. I accept that this may not concur with the official definition of transmission (I am certainly not a learning theory expert).

This leads me to wonder about a more conventional example of instructivism: the university lecture. When the lecturer is delivering his or her monologue, are the students not interpreting the transmission?

Thanks Ryan,

I think your question hits on a problem in the use of ‘constructivism’ in general as a theory in learning and teaching and at the same time addresses the main criticism of ‘instructivism’, which is that the instruction is designed as if the learner were simply a sponge absorbing information, rather than as an individual interpreting a message with an existing schema (life history, previous experiences etc.). So yes, I think the learner could interpret the lecture in a different way than the lecturer intended (which is why clickers and Echo’s Lecture Tools are great because they help address any misunderstanding during the lecture).

In regard to constructivism, it’s a theory of learning and cognition not necessarily a theory of teaching and as Jonathan Osborne says in Beyond Constructivism, it is too often used to attempt to teach ‘old knowledge’ (as if it were new, i.e. ‘discovery learning’) rather than to explain the creation of ‘new knowledge’, as I think it was intended. So ‘constructivist’ pedagogy, in a way I think might be a misapplication of ‘constructivism’ as a theory.

I’m not a learning theory expert either, I guess I’m just exploring like the rest of us. I studied constructivism a couple of years ago at Sydney Uni with Prof. Richard Walker in the school of education for (my soon to be completed, only a couple of months away) MA.

I’m not sure I buy into either of these theories, but I think they are food for thought. I’ve found, practically, thinking about and discussing them helps to sharpen your own view about design as I see you also do. They are a useful tool to add to the kit!

I have found this article very helpful. Am in preparations for an exam, where am required to look at Instructivism and constructivism and give a personal position. Very helpful indeed. Splendid work!

Thanks for letting me know, Prince. I’m glad I could help in some way.

In regards to instructivism, another article that may interest you is “Let’s get rid of the instructors!” https://ryan2point0.wordpress.com/2014/09/09/lets-get-rid-of-the-instructors/ :)

Wonderful Article. I really enjoyed reading how you placed the three together and show how they complement one another rather than take over. As the world evolves with technology and demands for education grow it has sparked the development of new theories. These new theories do not have to take an old theories place but rather it can add too and enhance those that already exist. We cannot get rid of instructivism as it is the foundation of education. Instead, using constructivism and connectivism to enhance instructivism focuses teachers on the current needs and directs them into the future of education.

Well put Veronica!

I don’t know why L&D have this predisposition to new things replacing what came before instead of enhancing it. To my mind, each approach is simply another tool at our disposal, to be used where the content, context and learners suit them best. There is no one way.

Well said Neil!